Having recently completed my first complete mod for Skyrim - a level pack, made up of five scenes from the neighboring city of Jehanna - I've decided to share my development notes here. The experience has been quite eye-opening, so much so that I'm taking a break from multifaceted-but-oh-so-limiting Unity to focus on work with Creation Kit and other dedicated studio tools. More thoughts on this in a future post, but for now: diagnostics on each level, one step at a time.

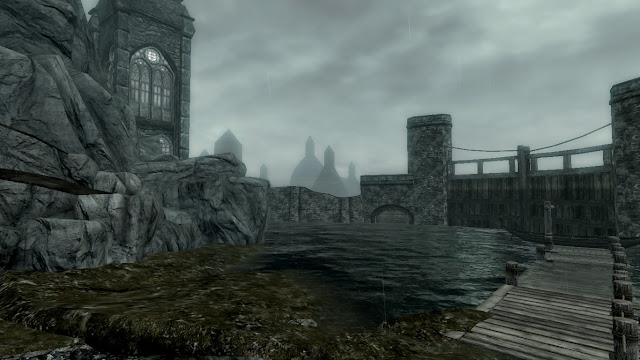

Overview: Designed to add some complexity to a standalone archer encounter, this tall, open map plays with vertical cover and narrow walkways to make arrows a greater threat.

Ingredients: 2 Riften Marketplaces, various Riften canal pieces, 1 Solitude Windmill, and a dam concocted from inflated Dwemer walls and gates.

Light Settings: Standard rain FX. While the following scenes use heavy fog in an attempt to simulate a rainstorm, the more realistic outdoor rain was used here to set the stormy mood.

1: A rainy dock, surrounded by a low, broken down seawall. To the foggy north, vague LOD buildings are barely visible through the storm.

2. The entrance to a deep canyon. The mud-caked road slopes upward here, before revealing itself as part of a rickety wooden canal. On the right, the creaky wooden back gate of the reservoir, at the foot of which is dead bandit littered with Orcish arrows.

3. A rough hole in the wall leads to a narrow drainage chamber, with a gash in the ceiling illuminating the misty condensation. Drips from the ceiling are everywhere - almost as if it were raining inside, were such things possible. A Dwemer pipe leads to the west.

4. The bottom of a towering reservoir, the shapes of Orcish and Nordic buildings dimly visible on the cliffs above. This uneven canal winds through the lowest levels of the reservoir, only offering vague glances at the structures above, including a pair of steam-belching heating pipes.

5. "What was that?" calls a voice from above. A Reachwoman archer dashes across a makeshift wooden bridge, and starts taking aim. She is an unusually nimble dodger, and with her high ground making for easy cover, is set to pierce yet another bandit skull. The creaking walls appear to take the sound of eerie, animal cries - or perhaps it's just a carefully applied, audio distorting, illusion spell?

6. Evading her, however, is easy enough. The canals offer easy getaway, provided the deepwater areas are avoided. In two spots near the east end of the room, caked mud and Dwemer pumps can be climbed, putting the player on equal ground.

7. The higher level of the reservoir, made up of three flat areas connected by wooden walkways. The archer from earlier - revealed via CHIMscan to be named Satie Madmarche - is nowhere to be seen, but groups of her pet Red Elk can be found grazing fresh brush. While aggressive, the female elk will only attack if their space is violated, while the males will corner any who dare intrude on their territorial pissing grounds, hitting them with a barrage of knockdown attacks.

8. A perceptive and pacifist-leaning player might detect that Satie is only defending her territory as well, and sneak into the windmill - torchlit to designate it as an exit - undetected. But most bloodthirsty Nord heroes will no doubt be scrambling along the walkways, trying to find a way past the bridge-blocking Bull Elk in search of a memorable fight. Up here, Satie's arrows are a bit more dangerous, with limited space for sidestepping. Cornering her, or knocking her below where she loses her advantage, can even the playing field a bit.

9. Careful sneakers and thrillseeking murderers alike can find Satie's camp here, which offers loot, a comfortable bed and firepit, and a diary offering her somewhat tragic backstory - hopefully, tainting the thrill of victory with a healthy dose of bittersweet guilt.

Commentary:

An early level, and home to some classic novice missteps. As should be obvious, the scale is more than a little ambitious, and the large central area limits the ability to roombound - meaning framerate drops are hard-wired into the stage's DNA. When learning a new toolset, it's arguably more important to figure out what *can't* be done instead of merely what *can*, and a recklessly ambitious design like this certainly yielded a few hard lessons.

Once upon a time, the central area was more enclosed, with smaller walls blocking off sections of the main pit - an attempt to safeguard against long view distances, but one which simply doesn't work with large, multisided pieces like these Riften Marketplaces. Opening it up did enhance the general flow, and also creates an incredible sense of scale - although there's definitely a cost performance-wise, and I can't imagine attempting a layout like this, knowing what I do now.

The drainage canal through which the reservoir is entered is a frustratingly linear area, hastily assembled after a few fumbled starts. This budget solution does get the player from one key point to the next, but only by cheaply pushing them through a relatively ugly corridor, far too early in the scenario for such a misstep. A more subtle flaw lies in the attempts at makeshift walkways, which match too closely with the Riften set used on the walls, and therefore don't look at all like something assembled by one woman and four Elk, in a few turbulent weeks.

On the topic of Satie and her pets - they're the real stars here, and on most plays outshine the flaws of the setwork. Archers in Skyrim tend to be used in support roles to melee enemies, but here, this relationship is inverted, with relatively weak close-range units blocking player progress and trying to knock the player into positions where arrows are unavoidable. The encounter also has some healthy moral complexity - most players will probably attack someone resembling a Forsworn bandit on sight, but any who read Satie's diary will likely find themselves wondering if a confrontation was in fact necessary. As nonlethal options are becoming one of the most fascinating (and sparsely explored) frontiers of gaming, encounters which raise questions of necessity have an inherent memorability, which sets them apart from the old fashioned "kill all the bad guys" school of level design.

Many of the outdoor illusions in this scene would have no doubt worked better in the context of a worldspace (something I didn't feel comfortable touching on a first mod) - as it stands, there are a number of inconsistencies with the following area, though they may only be noticeable to detail-obsessed level designers like myself (and possibly, yourself). While most of the scenes in this piece pride themselves on economic lighting choices, this one uses outdoor lighting to achieve the mood-setting rain effect, which renders the few lights used less effective - possibly even redundant.

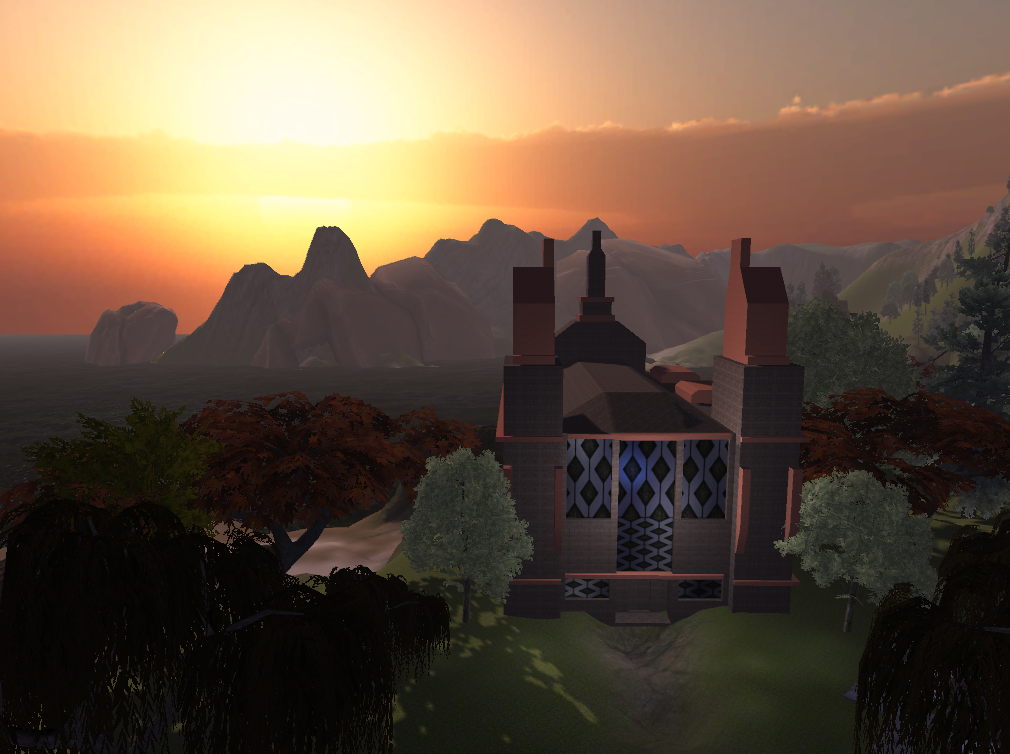

Premise: Inspired by the ruins of the old Los Angeles Zoo in Griffith Park, this exploration-themed level is probably the best laid out of the batch - which isn't saying much, as it's pretty jumbled and would benefit from a redesign. The player makes their way from an elevated canyon (A), down a long cramped stairway which leads into the first, and largest, cage area (B). Once outside, they find a road washed away by a flooded river (C), which leads past some smaller cages (D) and into a wooden observation platform (E). From there, they can take the staircase at the back of cage F, and leap over points G and H to make their way to the rooftops of the cages explored earlier.

Premise: Inspired by the ruins of the old Los Angeles Zoo in Griffith Park, this exploration-themed level is probably the best laid out of the batch - which isn't saying much, as it's pretty jumbled and would benefit from a redesign. The player makes their way from an elevated canyon (A), down a long cramped stairway which leads into the first, and largest, cage area (B). Once outside, they find a road washed away by a flooded river (C), which leads past some smaller cages (D) and into a wooden observation platform (E). From there, they can take the staircase at the back of cage F, and leap over points G and H to make their way to the rooftops of the cages explored earlier.